Hack Watch: So About Those Rate Hikes...

Few of the pundits who sprang to Jerome Powell's defense last year have acknowledged that their analysis was exactly wrong.

Welcome to Hack Watch from the Revolving Door Project. This (hopefully) weekly newsletter will document the conflicts of interest, perverse incentives, and just flat-out wrong analyses endemic to the 90’s types whom the mainstream media turns to for quotes about the economy far too frequently.

Interest Rates Aren’t His Children, But He Will Raise Them

On Wednesday afternoon, the Federal Reserve announced it was hiking interest rates by 75 basis points (0.75%, 1bp = 0.01%). More importantly, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, in his press conference discussing the rate hike’s announcement, promised to “keep at it,” making it clear that the central bank isn’t done yet. The Fed is now projecting that rates will rise further up to about 4.4 percent, a whole point higher than it projected in June. This comes as reticence from economists and business leaders is building.

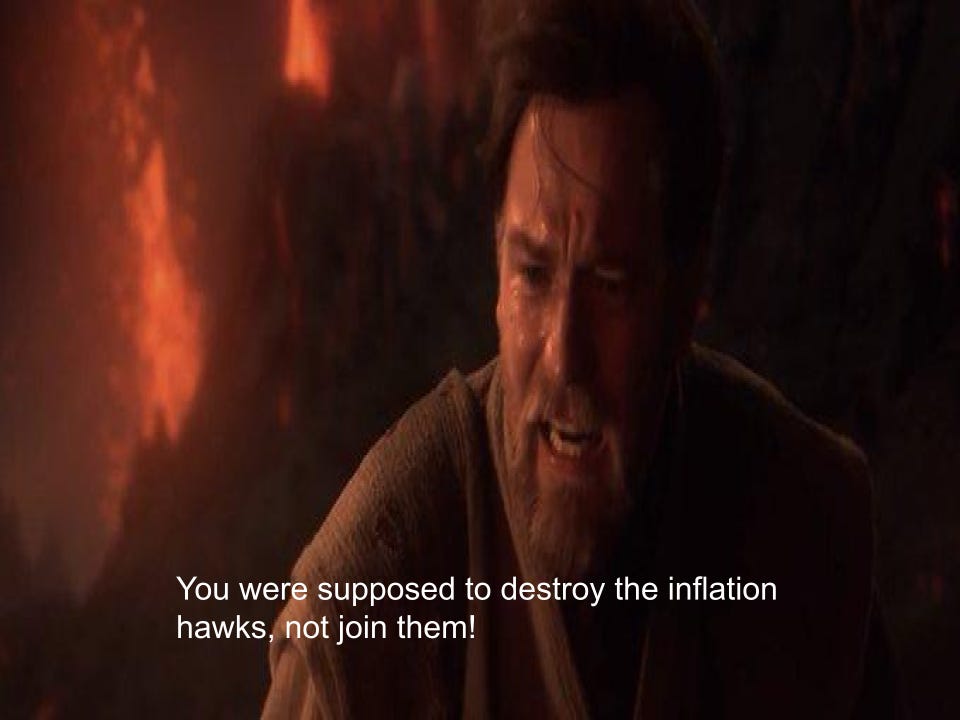

The whole thing is pretty frustrating for those of us who spent all of last year arguing about whether President Joe Biden should renominate Powell or tap a new chair. The Revolving Door Project was firmly on team “Dump Powell.” Team “Keep Powell” won, primarily by pointing out the dovish trend of Powell’s monetary policy up to that point. Now, Powell has shifted from a hero of the inflation doves to being openly compared to Paul Volcker by his own biographer.

How did we wind up here? Well, a big part of it is that the usual assortment of chin-stroking white male pundits saw an opportunity to punch left and pounced on it. Few of them have since acknowledged that their analysis, written to belittle anyone who disagreed, has proven exactly wrong.

RDP’s Argument

Last year, we argued that there were causes for concern about a Fed helmed by Powell. On monetary policy, his history seemed to indicate more of a commitment to doing whatever was least controversial at the time, rather than any particular commitment to full employment. Beyond that, Powell was, at best, disinterested in the regulatory role of the Fed, which is the single most important federal regulator of banks in addition to its monetary policy role.

We want to be responsible and not misrepresent ourselves as perfect oracles on Powell. Our argument that Powell’s commitment to low interest rates was tenuous was mostly secondary to other criticisms: his disastrous record on financial regulation, the massive ethics scandal under his tenure (whose protagonists have faced few consequences for it), and more. For the most part, we chose not to directly challenge the consensus within the economics profession at the time that Powell’s tenure up to that point had led to a sea change in monetary policy. But we were less than convinced that Powell, a career private equity lawyer at a firm with a long history of union-busting, was especially committed to workers.

If anything, we at RDP saw Powell’s dovish posture as a ploy to make a renomination uncontroversial among Senate Democrats. This seemed to be confirmed by an abrupt about-face one week after he was renominated. The credit afforded to Powell for an emphasis on full employment was also odd given that it was mostly a continuation of the stance the Fed had adopted under his predecessor, Janet Yellen. (Tellingly, Yellen met with union leaders throughout her tenure at the Fed, but Powell never has.) Meanwhile, there were other potential picks for chair whose history proved they were more committed to full employment and stronger bank regulation. Since the end of the nomination fight, the bank oversight component has completely vacated the headlines. Inaction is never newsworthy until you’re in a crisis.

Powell opponents, including ourselves, gravitated around Lael Brainard when it became clear she was the only alternative Biden would consider. It’s true that she hasn’t resisted Powell’s hawkish turn — but we all know the Chair at the Fed wields both carrots and sticks to get the Governors into public unanimity. Dissents are rare, not due to perpetual FOMC mindmelds, but because of the coercive power of bizarre norms and real powers, such as the Chair’s influence over which staffers are allowed to work with which governors on what projects. As the early chapters of Christopher Leonard’s The Lords of Easy Money document, Fed culture places an enormous premium on presenting a united front to the world, and any open disagreement on policy leads to alienation and internal condemnation.

That’s not to say we have any insight into Brainard’s private thoughts on Powell’s new hawkishness. Heck, we’ve never been Brainard stans. We opposed her potential bid for Treasury Secretary, since her history evinces reason for doubt on that agency’s issue portfolio. But Brainard’s history at the Fed showed she was much more trustworthy on the central bank’s policy areas — monetary policy and financial regulation. We don’t love Brainard, we just preferred her strongly over Powell.

To the best of our knowledge, we were the first organization to argue against his renomination in a piece in early May 2021. In the subsequent months, different voices offered different versions of the case for him (more on that later).

But the loudest and most influential pro-Powell takes came from a host of bloggers and magazine writers who parachuted into the issue as soon as it was clear there was an intra-Democratic fight brewing. These arguments had less to do with Fed policy knowledge and measured consideration of political-economic uncertainty, and more to do with absolute glee at the opportunity to punch left. Pundits relished the chance to run to Powell’s defense, presenting themselves as the allies of workers and progressives as out-of-touch elites.

The Hacks Hack Away

Josh Barro fumed that “The arguments for firing Jay Powell are tiresome and stupid.” He wrote rhapsodically of Powell’s supposed pro-worker stance. “You need someone with a commitment to pro-worker monetary policy at the head of the bank in the face of concerns about rising inflation,” he declared. (You sure do, Josh!) Barro proclaimed that Powell’s “staid, bankerly image” was how he’d pulled off “a bold shift in monetary policy, and yet he does not come off as a radical to anyone.” Per Barro, “Powell has worked assiduously to build respectful relationships on both sides of the aisle on Capitol Hill, and the personal trust he has built has quieted political criticism and given the Fed more room to operate.”

We began calling this “The Argument From Jeopardization”: that daring to criticize Powell would jeopardize the hard political work he’s put in to popularize dovish monetary policy — political work that we all just had to take the pundits’ words was definitely real, because it was all behind closed doors, and there was no actual reporting to substantiate the claim. There were any number of reasons Powell might have been knocking on doors on the Hill in the months before his renomination — like, say, promising those conservative Senators he’d hike interest rates if they voted for his renomination. But, the pundits proclaimed, trust us, this guy’s legit.

Our old friend Matt Yglesias also guffawed that “The Progressive Case Against Powell Is Weak.” Initially, Yglesias was sympathetic to the view that a Democratic President should have a Democratic Fed Chairman, but promptly changed course once an opportunity to punch left arose. Yglesias felt Powell earned another go-round since “With an assist from fiscal policy, he helped guide what was almost certainly the world’s strongest and most robust economic response to the Covid pandemic.” (Yglesias now insists that fiscal and monetary policy is the main culprit behind inflation, despite empirical studies to the contrary, and praises Powell for reversing course.)

We called this “The Argument From Performance.” The thing is, keeping interest rates low during the sharpest economic downturn in history is Macro 101, a bar so low that it is on the figurative floor. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, a man who knows a thing or two about macroeconomics, wrote that “Almost anybody reasonable would have done something similar.”

Throughout the fight, Yglesias also revealed either stunning ignorance or eye-popping disinterest in fact-checking and proofreading — neither is a good look for a journalist, or wonk, or blogger, or however Yglesias is branding himself this week. First he referred to the Federal Communications Commission as a financial regulator, which it just isn’t. Later he said regulation should be left up to the “Vice Chair for Regulation, where we also have a Trump-era holdover in Richard Clarida.” The job is called the Vice Chair for Supervision, and the job-holder at the time was Randal Quarles.

Then there was the enviro-bashing. Plenty of green groups stood up to the “renominate Powell” drumbeat on the grounds of his poor climate finreg policies, which was especially relevant at the time since the Fed was really the only thing keeping the fossil fuel industry from going under. But even dedicated environmental reporters couldn’t resist the opportunity to punch the tree-huggers when a rich Republican with a fancy job title wanted them to.

Robinson Meyer at The Atlantic tut-tutted that “the planet cannot afford a climate movement that is so ignorant about the economy” as to oppose Powell. He argued that full employment was a necessary component of transitioning to a green economy, and claimed that only Powell could deliver it. “If Powell is replaced by a Democrat, there’s no guarantee that his successor would continue to keep interest rates low,” Meyer wrote, neglecting that there was also no guarantee a Republican weathervane like Powell would keep them low either.

Second, he claimed environmentalists’ “fear of getting their hands dirty with political trade-offs” was leading them to partner with “groups and interests that would make decarbonization impossible” like, apparently, financial regulation hawks. On the contrary, until Congress passes a law immediately banning and winding down all fossil fuel development, and the White House staffs a Department of Justice ready to go to legal war on all fronts for the planet, climate-focused financial regulation will be an indispensable tool for actually achieving decarbonization. (It will still be after that, too.) As Meyer claimed, “the left’s dream of passing a Green New Deal would immediately become impossible” in a high interest-rate environment. But framing this as a trade-off against tight financial regulatory policy is a false choice. Under Powell, we may now get neither from the Federal Reserve.

The Good-Faith Case For Powell

To be clear, some voices in the pro-Powell camp engaged in good faith with his critics and advanced thoughtful considerations of all of the elements that should go into picking a Federal Reserve Chair. We enjoyed a very fruitful back-and-forth with our CEPR colleague Dean Baker, a strong Powell supporter, but one who based his endorsement on decades of closely studying the Fed, as well as due, respectful consideration to the arguments against him. We learned a lot from Dean’s perspectives, and hope that he feels the same about ours.

For instance, as Dean noted, Powell was at the helm while the Fed embraced concerns around asymmetrical impacts of tightening monetary policy on vulnerable communities. Similarly, he promised not to hike rates until we neared full employment. And he considered full employment to require unemployment well below the 5% level that had been precedent. These are good points. Powell may have been a hawk in dove’s clothing, but he wore the outfit well. This morning, Dean had an article in The Guardian discussing how rate hikes now threaten exactly the type of damage Powell was supposed to head off.

But Dean’s more reasonable take that credited Powell with some important but wonky changes requires a level of understanding that runs contrary to the modus operandi of the elites of economic punditry. The writers detailed above are read far more widely and by far more powerful people consistently than Dean. They suddenly decided they’d become Fed-watchers, and wrote paeans to Powell and his supposed covenant with working people.

Did The Pundits Get Played?

This is why policy debates require considering substance over stature. We do not know who whispered in these and other pundits’ ears about Powell, but the Fed is an agency notoriously obsessed with its own public relations. It has to be, since vaguely signaling rate changes in the media months in advance, without actually announcing clear policies, is key to ensuring Wall Street traders don’t all buy or sell stocks or bonds at once, which could overwhelm the system in a panic. That’s also why Fed culture is so obsessed with unanimity among the governors; signs of internal dissent could cause major market fluctuations. Fed Chairs are notorious for controlling the press’ access to them, but being frank and friendly with a few trusted journalists. They’re shrewd at trading access and scoops for assurances, implicit or not, that they’ll get reported on exactly the way they want to.

This intense focus on public relations can lead to some perverse outcomes when the personal politics of renominations comes into play. As our Max Moran reported for The American Prospect last October, the Fed’s longtime press secretary, Michelle Smith, is also its chief of staff, head of congressional affairs, top liaison between the Board of Governors and the staff, and director of the staff economists. Smith, a communications professional, wields extraordinary power over everything that happens at the Fed, and she answers only to Powell.

We are not alleging some vast, conscious conspiracy between the Fed and the media to ensure Powell’s renomination. The truth of politics, finance, and the media is nearly always vastly more mundane than that. We simply wouldn’t be surprised if Smith did what she does best: play on some writers’ outsized egos by providing tips and an off-the-record interview or two in service of her boss’ goals. Whether or not Smith herself was involved, it’s also probable that Powell wielded the skills she’s helped to teach him.

Where Do We Go Now

Whoever worked the press on all of the pro-Powell pieces, their talking points are pretty clear: hit the “low interest rates” and “bipartisan Republican” points hard, and, ah, imply that Powell won’t take a Volckerish heel-turn if renominated.

But Powell has taken a heel-turn. Low-wage workers and people of color, who did nothing wrong and probably know nothing about these Beltway games of politics and prestige, will be left to suffer for it. Powell endorsers like Barro, Yglesias, and Meyer claimed that they supported the man out of certainty he wouldn’t raise interest rates, despite pressure from inflation hawks. Now that he has, we hope they’ll show some consistency and oppose Powell and the further suffering his policies will entail — indeed, the suffering that is their explicit goal.

Progressives are often chided not to “let the perfect become the enemy of the good.” The adage is an important reminder of feasibility. But it needs a corollary; don’t let the half-decent become the enemy of the good, either. Just because it looked like Powell was a dove doesn’t mean that the alternatives weren’t any better. Some rate hikes may have been inevitable, but sans Powell, they may have been hiking rates in 50 bp intervals. Believe it or not, it’s important not to merely settle for the status quo.

Maybe a Lael Brainard-led Fed would have acted largely the same. But that’s a matter of probability. It was much more probable that a Powell-led one would, and it has.