Another Win For The UAW Means Another Loss For Centrist Pundits

Will the auto union’s latest victory get Yglesias to reconsider his position on labor?

Last Friday, the United Auto Workers (UAW) notched a big win by unionizing a Volkswagen plant in Chattanooga, Tennessee. The election was a landslide, with 73 percent of eligible workers voting in favor of joining the union. This historic drive rectifies two prior failed attempts in 2014 and 2019, and marks the first time the UAW has unionized a Southern auto facility by election since the 1940s.

The UAW has been on an impressive run lately. Last November, after six weeks of rolling strikes, the union was able to secure significant concessions in its contract negotiations with the auto industry’s Big Three. The organizing for the Big Three contracts and the Chattanooga Volkswagen plant election are both emblematic of a broader resurgence in American labor organizing these past few years. In various industries across the country, employees have agitated for—and often earned— higher wages, safer conditions, and greater autonomy in their workplaces through collective action.

This upswing in worker power has been an obvious thorn in the side of bosses, but they aren’t the only ones feeling dismayed. Anti-union politicians, like Tennessee’s Republican Governor (and former air conditioner mogul) Bill Lee, tried in vain to dissuade Volkswagen workers from making the “mistake” of joining the UAW. (Fun fact, none of the nearly 1600 people that work for Lee’s family business, The Lee Company, are unionized.) Likewise, centrist pundits have been quick to temper the expectation of a rightfully enthusiastic working class. Which brings us to this week’s hack: Matthew Yglesias.

In January, Yglesias wrote a piece in Bloomberg that attempted to spin the UAW’s triumph over the Big Three as, actually, a win for nonunion manufacturers. By announcing wage increases somewhat in line with those now in place at Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis, Yglesias argued that Elon Musk successfully undercut unionization efforts at Tesla by “essentially offering nonunion workers the vast majority of what they could have won with a contract.”

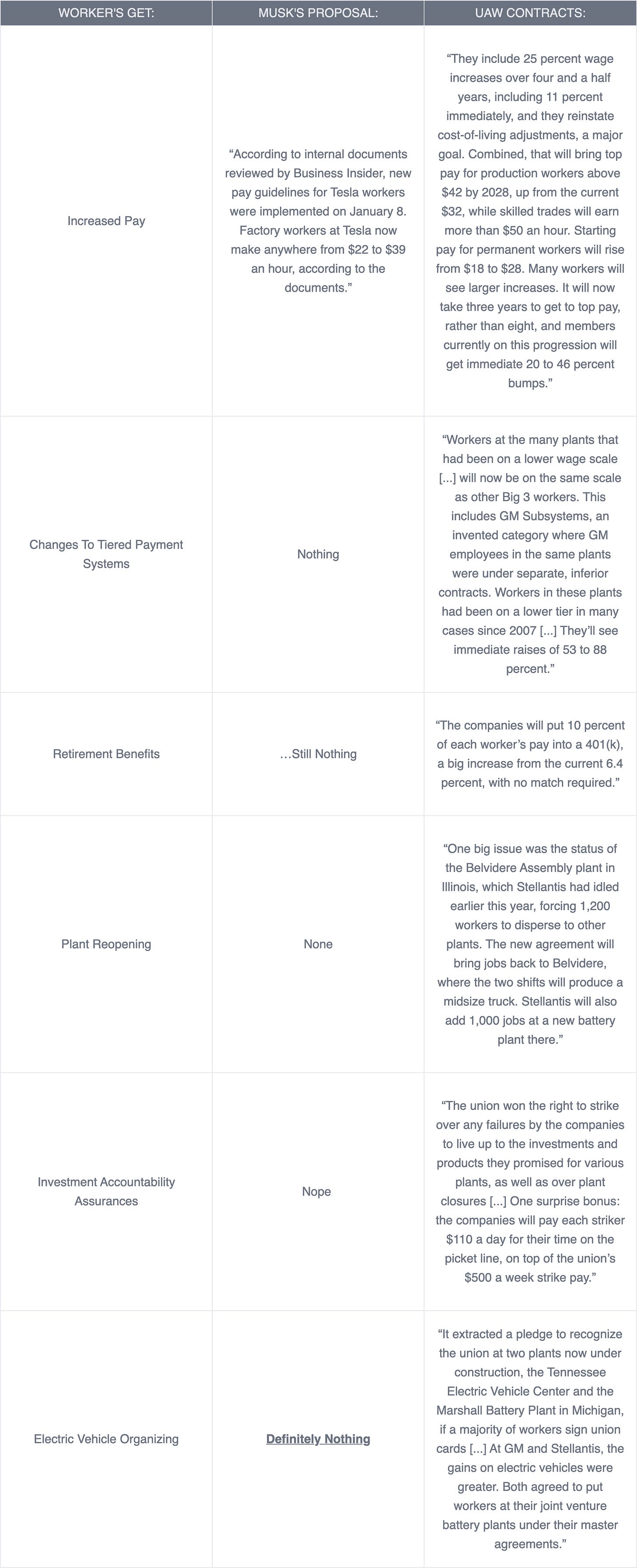

To call increased wages “the vast majority” of what workers stand to gain from collective bargaining is false. More importantly, hyperfocusing on pay above all else is a tactic used by bosses, and their sympathizers in the media, to hand wave away the benefits of a union. Even on the question of wages, though, Yglesias is wrong. Tesla’s pay range for all employees would still be between $22 and $39 hourly, while UAW workers can start as high as $28 and earn much more down the line.

A simple comparison between Musk’s proposal and the UAW’s new contracts would easily disprove the notion that raises constituted the core of the union’s successful demands. Yet, Yglesias refused to make that comparison. Don’t worry though, Matthew, I’ve done it myself:

While we can’t know for sure the reasoning for such an omission, I suspect it has something to do with Yglesias’ argument benefiting from ambiguity. Should readers learn that striking workers extracted the above (and other) concessions from auto executives, they’d be less inclined to believe that a single pay bump (that still falls short of the UAW’s standard) is enough to stifle organizing at Tesla.

Which then begs the question: besides pay, what are some of the other reasons why unionizing the electric vehicle maker has proven so difficult? According to Yglesias, the supposed politicization of the labor movement is to blame:

“The point is not that political ideology has no role to play. Labor organizing wouldn’t work without some level of ideological motivation; someone has to do the initial work for reasons broader than personal self-interest. The risk is that the more political the labor movement becomes, the more difficult it is for unions to perform their core functions [...] American unions have long walked the line between broad left-coalition politics and the representation of narrow member interests. The more unionization becomes a project by ideologues, however, the more it becomes a project of ideologues. That reduces its potential appeal and strengthens the hands of anti-union managers.”

Whereas more in-depth—and dare I say actual—reporting on the issue posits everything from Silicon Valley start-up culture among the workers to rampant and illegal union-busting activity by Tesla management, Yglesias instead looks for answers in his boilerplate brand of left-punching. Anyone familiar with Yglesias' “coverage” (read: hot takes on social media) of the UAW will immediately recognize this line of attack.

In the aftermath of Shawn Fain’s victory in UAW leadership elections last year, Yglesias took to Twitter, to discredit the union’s new president. Yglesias’ habit of posting then quickly deleting his more inflammatory opinions makes quoting him in full nearly impossible. But if this response thread and other UAW-related post are any indication, one can assume the original take had to do with Fain ostensibly being more in line with the union’s graduate students than its factory workers. Such comments echo the sentiment Yglesias expressed in the Bloomberg piece: that the biggest impediment to labor’s success are lefty ideologues hijacking the movement, rather than, say, a political economy that disproportionately favors the interests of executives over workers. If this were true however, I highly doubt we’d be seeing the UAW continue to boost its ranks, especially in the South.

(Yglesias should also question whether his assumption that the poorly paid highly educated and the poorly paid less educated have nothing in common. Even if straight Marxism can be mocked…so can the reflexive exclusion of material economic reality from consideration of class and social status.)

In general, the idea that the “far left” position and what is optimal within “populism” are inherently irreconcilable is…not true. Biden’s populist attack on corporate “junk fees” has been adjudged enormously popular by Silicon Valley titan Reid Hoffman’s prominent political shop Blueprint, among many others. As the group urging the Administration to undertake a “corporate crackdown,” we’re not surprised. Indeed, evidence that Obama’s 2012 message against Romney remains popular and applicable against Trump in 2024, including the focus on raising taxes on the rich, abounds.

So it is not surprising to us that Shawn Fain, a man famous for a terse message—“Eat the Rich”—was able to mobilize solidarity strong enough to stare down the Big Three and to make inroads to workers in the inhospitable South. So why is it so surprising to Yglesias?

As a centrist pundit, Yglesias functions less as a reporter of the news and more as an interpreter. And his interpretation of the current labor landscape looks increasingly suspect as of late. If he is unwilling to update his outlook, policymakers and other media figures alike should ignore his “expertise” on the matter and look elsewhere for insights.